CAN THE MUTED SPEAK? Kathy-Ann Tan on Satch Hoyt at MARKK, Hamburg

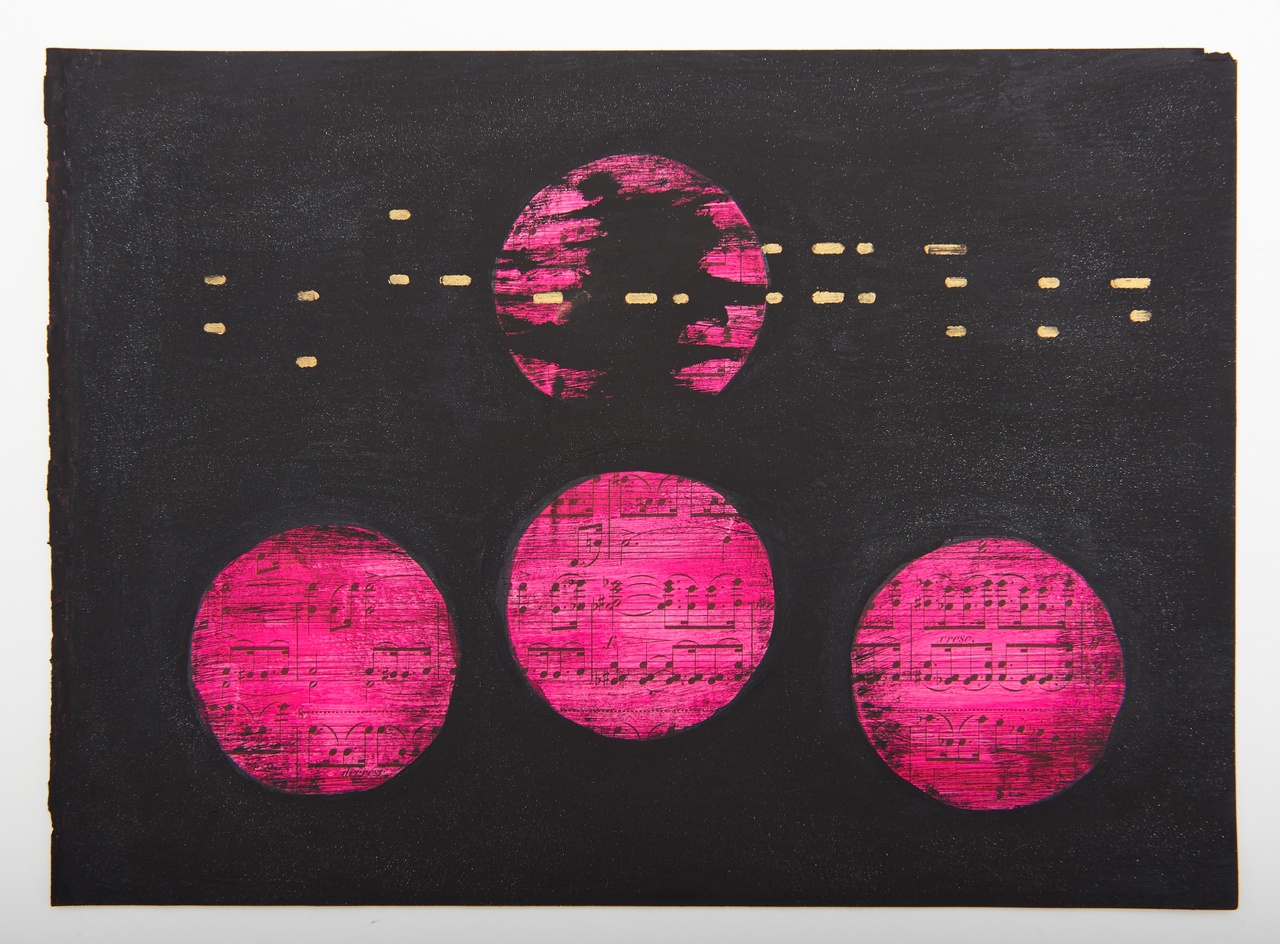

Satch Hoyt, “Black N Pink,” 2023

“Un-Muting. Sonic Restitutions” at the Museum am Rothenbaum – Kulturen und Künste der Welt (MARKK) is the latest installment of the artist and musician Satch Hoyt’s longstanding and multi-chapter project “Afro-Sonic Mapping: Tracing Aural Histories via Sonic Transmigrations.” Launched in 2016, the latter began with research into phonographic recordings made by European anthropologists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries of “traditional” music from the region currently known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola. Bringing these sound clips to musicians in Luanda, Salvador de Bahia, and Lisbon, Hoyt created spaces of collective encounter, conversation, connection, and the creation of new music in response to the earlier recordings. Following an exhibition in November 2019 at Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin and a publication in 2022, Hoyt’s “Afro-Sonic Mapping” project continues to grow and take on different iterations and forms, the latest of which culminates in his recent performance and current exhibition in Hamburg.

“Un-Muting. Sonic Restitutions” can be understood as an artistic intervention in two ways: first, it is a spatial intervention into the topography of the museum, occupying the “Zwischenraum” that was originally conceived as an interactive exhibition and discursive program space that invited visitors to help the ethnological museum with its efforts at institutional critique, repositioning, and change. Second, it is a performative intervention into the institution’s African collection, which encompasses roughly 260,000 artifacts including masks, fabrics, sacred objects, jewelry, and around 600 musical instruments. [1] These objects were largely collected and donated by Hamburg merchants and seafarers involved in the colonial plantation economy, who traded colonial loot plundered from the African continent, in particular West Africa, in the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries. As part of the project “MARKK in Motion,” which began in 2019 within the framework of the Initiative for Ethnological Collections funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation, Hoyt was invited by the museum to work with its archives. His research led the artist to the process of selecting several musical instruments in its African collection that he would performatively “un-mute,” hence symbolically enacting a form of “sonic restitution” that counters the colonial violence of keeping these instruments silenced and forgotten in the museum. [2]

Satch Hoyt, “Sacrificial Lamb,” 2016

In this respect, “Un-Muting. Sonic Restitutions” at MARKK is reminiscent of “Mining the Museum,” Fred Wilson’s landmark 1992 intervention into the archives and collections of the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore. [3] In “Mining the Museum,” Wilson was given a free pass to delve into the MHS’s inventories, and to select objects that he would visually arrange in different and provocative configurations. This led to unsettling juxtapositions such as a whipping post where enslaved persons were tortured being placed in front of four ornately carved 19th-century wooden armchairs, hence forming an arena of brutal spectacle, or the pairing of a set of ornamental silver teapots right next to a set of iron shackles. Viewers were confronted with the sheer depravity of colonial violence, and the exhibition also exposed the selective and biased narrative that institutions of colonial display (ethnological museums, historical societies, and the like) tend to offer their visitors under the pretense of “historical facticity” and “neutrality” – narratives that oftentimes merely reproduce colonial violence in the name of art, heritage, and culture.

The latest installment of Satch Hoyt’s ongoing “Afro-Sonic Mapping” project reflects the artist’s dedication to intervening in the spaces of museums and institutions with troubling colonial legacies and his seeking to connect African diasporic communities through the power of sonic frequencies. Conceptually similar long-term artistic research projects come to mind, such as Grace Ndiritu’s “Healing the Museum”. In 2012, the British-Kenyan artist began to combine ritual, practices of shamanic healing, and live performance to posit the notion of the exhibition as a form of embodied architecture that transforms, “re-Indigenizes” (Cat Dunn), and ultimately heals the space of the colonial museum. Like the various chapters of Hoyt’s “Afro-Sonic Mapping” project, the multiple iterations of Ndiritu’s “Healing the Museum” also focus on site-specific interventions that have a strong participatory and performative component. “Healing the Museum” has seen various articulations at SMAK in Ghent, Belgium (its inaugural iteration as “The Opening,” 2012), the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (“Spring Rites: Birth of a New Museum”, 2014), Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (“Women’s Strike: Healing The Museum,” 2021) and Nottingham Contemporary (“Labour: Birth of a New Museum,” 2021), among others.

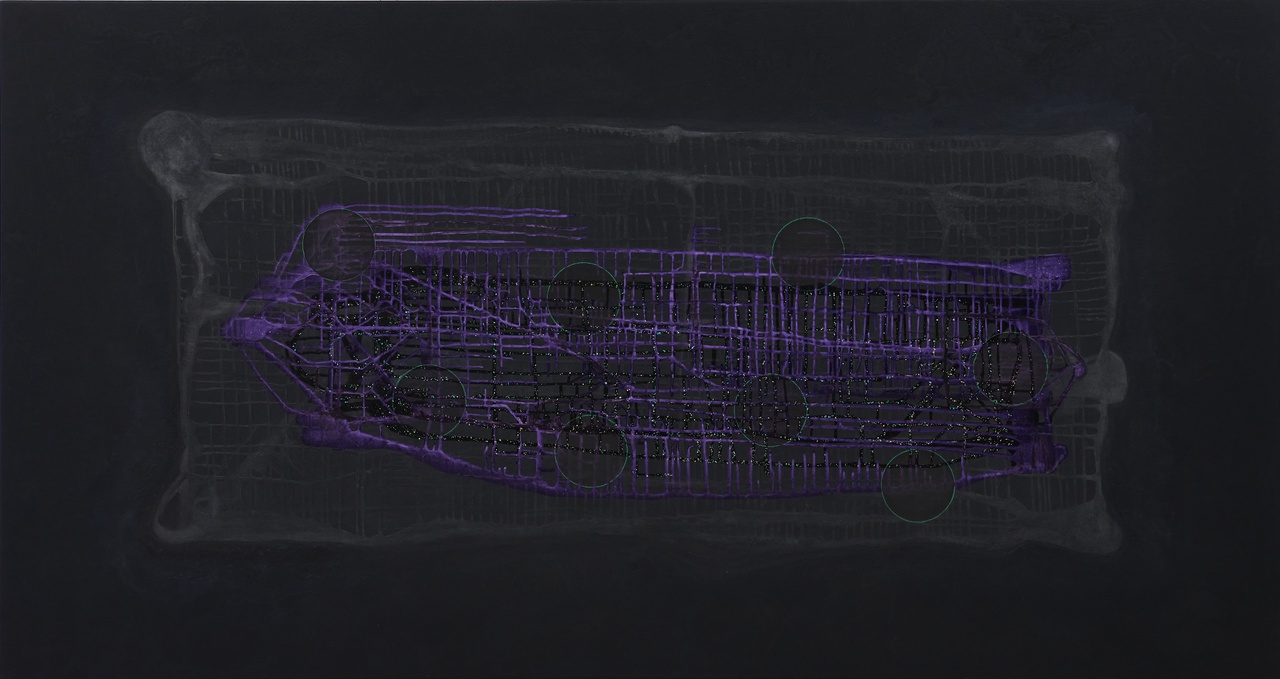

Satch Hoyt, “Purple City and Beyond,” 2023

Clearly, western cultural institutions continue to wrestle with their sense of white guilt, and their desire to collectively partake in the act of transformative justice (or, more skeptically, inviting artists to do the work of transformative justice for them) reflects their attempt at assuaging that guilt. This might sound harsher than necessary, but it does uncover the institutional dynamics that underlie much of the ongoing debates around restitution, repatriation, and reparation across Europe and North America. Because this debate is still led by white, Euro-American-centric, academic, intellectual, and cultural-political discourse, and hence filtered through this very lens, it reestablishes the power dynamics of coloniality and does not go far enough in terms of reparation for the organized theft, looting, and genocide carried out in the name of European colonial and imperial expansionism on the African, Asian, and South American continents for over five centuries.

Which brings us back to Satch Hoyt’s “Un-Muting. Sonic Restitutions” in Hamburg. The exhibition comprises: a curated display of nine musical instruments from the museum’s African collection [4] that are juxtaposed with the artist’s own object installation, Sacrificial Lamb (2016) – a golden trombone wrapped in black Persian lamb fur; the framed diptych Black N Pink (2023) created on pages from a Franz Schubert music score book; Black Urban Grid (2023), a large triptych of paintings with the pieces Purple City and Beyond, Urbanicity #1, and Urbanicity #2, and, last but not least, a video recording of the exhibition’s activation in the form of a live performance with the musician Dirk Leyers and Satch Hoyt as the latter “un-mutes” selected instruments from the museum’s African collection. The architecture of the exhibition is interesting, framed by satiny white drapes that can be pulled together to demarcate and carve out a space of sonic restitution with its black walls, Black histories, and Black ontologies, ensconced within the white ethnographic museum.

“Satch Hoyt: Un-Muting. Sonic Restitutions,” (performance with Dirk Leyers) MARKK, Hamburg, 2024

I came away from the exhibition with mixed feelings, mostly because of the realization that the “un-muting” of these musical instruments was short-lived or temporary at best, and that they themselves would likely never be repatriated to the geographic contexts from which they were looted (regardless of whether or not that repatriation was actually desired). As an overtly performative gesture that prompts more sustained and committed forms of institutional accountability whether it be repatriation, restitution or reparation, Hoyt’s intervention into MARKK’s African collection is certainly a timely constituent of his “Afro-Sonic Mapping” project. I wonder, however, if there is another way to engage with the history of colonial atrocities and demand more far-reaching, organized processes of accountability and reparation, rather than simply reading these objects through our anthropocentric lens and thus assuming that we have the agency to “unmute” objects that have been “muted,” admittedly, on our own watch. The latter seems almost too easy a way out – how can centuries of colonial genocide, violence, theft, and abuse be exonerated by performative gestures that take place at the invitation of these same colonial institutions of display, within their same colonial architectures, without there being any inherent structural change in how these institutions are managed and governed? I consider if there is a quieter and subtler, more poetic, way to “un-mute” or to speak, in the words of Dionne Brand, “not in words and in words and in words learned by heart, told in secret and not in secret, and listen” (“No Language is Neutral”). [5] I imagine that, under the right conditions, sound and music have a way of piercing through the stubborn and unrelenting politics of containment that western museums are still characterized by. In gesturing towards a Blackness that Fred Moten describes as “the extended movement of a specific upheaval, an ongoing irruption that anarranges every line,” [6] Satch Hoyt’s “Un-Muting. Sonic Restitutions” invites a collaborative practice of artistic and musical creativity, ancestral healing, Black fugitivity, and the freedom to imagine otherwise. Whether MARKK Hamburg is an apposite space for such a practice, as an institution that continues to function as one of the largest ethnological museums in Europe today, remains questionable.

“Satch Hoyt: Un-Muting. Sonic Restitutions,” January 25–September 15, 2024, MARKK, Hamburg.

Addendum: The artist would like it mentioned that, in addition to the public un-muting performance with Dirk Leyers, he had performed a private un-muting session at MARKK in which he made recordings of instruments that he played. These recordings will be arranged and mixed with new compositions as part of the artist's un-muting process. To date, two mixed compositions from other site-specific interventions in collections exist - one from the Brücke Museum Berlin and the other from the British Museum in London. These compositions will be released, and thus made publicly accessible, in an album with other tracks that will become an integral part of the artist's future Sonic Restitution performances.

Kathy-Ann Tan is a Berlin-based independent curator, writer, and founder of Mental Health Arts Space (www.mhasberlin.com), a nonprofit project space that centers the mental health, knowledge, histories, and narratives of BIPOC and minoritized artists and cultural workers. She is interested in alternative and sustainable forms of art dissemination, cultural production, and institution-building that are committed to issues of social justice beyond a merely representational model of identity politics. Tan’s practice revolves around creating spaces for conversation, sharing, and empowerment for BIPOC and minoritized communities in the arts and cultural scenes in Berlin and beyond. As a former full-time academic, she has extensive experience in teaching, research, publishing, and public speaking.

Image credit: 1. - 3. © Satch Hoyt; 4. Photo Niklas Marc Heinecke; all images courtesy of Museum am Rothenbaum – World Cultures and Arts (MARKK)

Notes

| [1] | A full inventory of these objects can be found online. The museum has added this disclaimer in red text across the document: “Please note that many designations in this list have been identified as faulty, outdated or as racist abuse since the inventories’ original conception.” |

| [2] | The exhibition wall text describes how the musical instruments in the museum had been treated with pesticides in order to preserve them, hence making them unplayable because they posed a health risk. For Satch Hoyt’s live activation of the exhibition on January 25, 2024, a selection of instruments were cleaned, and the “muted” instruments were performatively played or “un-muted” by the artist. |

| [3] | See the Maryland Center for History and Culture website page on the “Mining the Museum” project. |

| [4] | These objects are: a rattle from Mali from 1911, a wooden double bell from Cameroon from 1923, two sanzas from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Cameroon from 1907 and 1929 respectively, an iron double bell from the DRC or the Central African Republic that was “acquired” during the German Central African Expedition of 1910–11 that was financed by the Hamburg Scientific Foundation (Wissenschaftliche Stiftung), an ivory horn from the DRC from 1906, two hunting whistles from Guinea from 1911, and a balafon with two mallets from Mozambique from the 19th century. |

| [5] | Dionne Brand, No Language is Neutral (Toronto: Coach House Press, 1990), 34. |

| [6] | Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 1. |