Memory’s body. Marie Muracciole on “Retrospective” by Xavier Le Roy at the Antoni Tapiès Foundation, Barcelona, and soon at the Deichtorhallen, Hamburg

Xavier Le Roy, "Retrospective”, Antoni Tapiès Foundation, Barcelona, exhibition view (Foto: Linda Valdés)

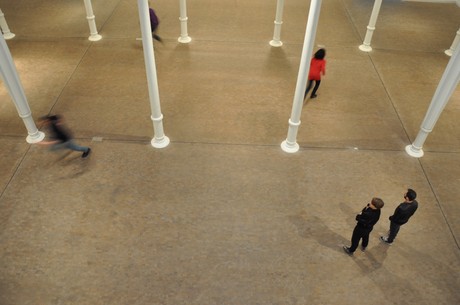

Xavier Le Roy, "Retrospective”, Antoni Tapiès Foundation, Barcelona, exhibition view (Foto: Linda Valdés)

When I dream, my body is the site, not only of the dream, but also of the dreaming and of the dreamer. In other words, in this case or in this language, I cannot separate subject from object, much less from the acts of perception. I have become interested in languages which I cannot make up, which I cannot create or even create in: I have become interested in languages which I can only come upon, a pirate upon buried treasure.

The dreamer, the dreaming, the dream.

I call these languages, languages of the body.

(Kathy Acker)

Having first taken place at the Antoni Tapiès Foundation in Barcelona in early 2012, Xavier Le Roy's "Retrospective” traveled the same year to the “Musée de la danse” in Rennes created by Boris Charmaz. [1] The show will re-open at the Deichtorhallen, Hamburg this next August. [2] Conceived as an answer to the invitation by Laurence Rassel, head of the Tapiès Foundation, the "Retrospective” was intended for a visual art exhibition space, and not with the goal of trying to melt into it. This first venue, an actual museum, was certainly a sharper contrast than the following ones, producing an interesting situation for the visitors and mapping some of the most rewarding possibilities in the dialogue between dance and art today.

Xavier Le Roy, "Retrospective”, Antoni Tapiès Foundation, Barcelona, exhibition view (Foto: Lluís Bover)

Xavier Le Roy, "Retrospective”, Antoni Tapiès Foundation, Barcelona, exhibition view (Foto: Lluís Bover)

Levels

By entering the main space of the Tapiès along the descending steps, viewers interrupted some of the action already taking place there and simultaneously reinitialized them: The performers, who were talking with visitors or carrying out a specific movement, would stop and run away. [3] They would come back briefly, and the new arrivals soon had one performer addressing them, telling them about him or herself and how he or she had entered into a professional dance practice in general and eventually with Le Roy’s work. Then he or she would describe and dance Le Roy’s approach to dance and its effect on the dancer’s own definition and practice of dance. The other performers would slowly take recognizable positions from different pieces of Le Roy’s, like “Self Unfinished” (1998), [4] where his body literally “rebuilds” itself over and over again, or “Le sacre du printemps” (2007), where Le Roy’s gestures seem to direct Stravinsky’s music, placing the spectators in the position of the musicians. But the most seminal work included in the retrospective was certainly “Product of Circumstances” (1999), a lecture-piece where the choreographer explains how he became a dancer after being a biologist, i.e. how he began to construct his “self” through choreography.

There are three levels in the architecture of the Tapiès: a main space, a circling balcony around the top of it, and another distinct space underground. From the balcony, all of the dancers’ actions were visible to the visitors as outsiders, like a theatrical device. In the space underground, archives and documents relating to Le Roy’s work were on view, and performers would answer the visitors’ questions. The viewer was thus invited to walk in and out in either direction between the three levels: a production-in-progress of what was a new piece (founded on the documentation of Le Roy’s approach in the performers' movements); the balcony from which to attend the display from the outside; and the behind-the-scenes of his projects as well as the archive. Adjoining the latter was a room in complete darkness. Recalling the anonymous piece “Untitled” (2005), where Le Roy covered human-size puppets in dark gray on a dark stage, mannequins clothed in grey sat all around, barely perceptible. Here, visitors were given a physical space in which to access invisibility and the Unheimlich. Arguably, this space could also lead to a misunderstanding of the show as trying to melt with the visual art vocabulary, being quite similar with a museum installation.

Xavier Le Roy, "Retrospective”, Antoni Tapiès Foundation, Barcelona, exhibition view (Foto: Lluís Bover)

Xavier Le Roy, "Retrospective”, Antoni Tapiès Foundation, Barcelona, exhibition view (Foto: Lluís Bover)

Holes

The conflicts arising from the presentation of dance within a museum was actually one of the main issues in this project. Le Roy is clearly a choreographer who doesn’t ask to be integrated into the visual art world through the category of “performance”. [5] He deals with “performing art” – theatrical practices in general – but stays focused on the body as his medium and the core of his work. He sometimes invades other contexts where he reconstructs dance, such as a research laboratory (“E.X.T.E.N.S.I.O.N.S.#1” and “#2”, 1999-2001[6]), a “scientific” lecture (“Product of Circumstances”, 1999 [7]), or a concert (“Mouvements für Lachenmann”, 2005 [8]), and now the museum. He explores these symbolic spaces and situations through a “gesture” producing meaning and resistance. In his quite renowned solos, an important part of his work, Le Roy diverts in issues of identification – enunciation, mimesis, mimetic, mimicry. In “Self Unfinished” (1998), using a few props (a chair and table, a boombox, a black dress, shoes, a pair of black trousers, a gray shirt), Le Roy enacts shifts of spatial and functional orientation, creating visual discontinuities with his own body that at some points become almost “impossible”. He rewrites his body’s function and image by making the spectator experiment with a form of indecisiveness, creating holes in his or her mental processing of visual perception. In the retrospective, this vocabulary of discontinuity in reconstructing the body was “acted out” through the interruptions of the performance, “translated” through the explanations given in the archive space, and “staged” through the separation of the three levels. Displacing the corporal schema with a spatial one, Le Roy activates the context of the museum as well as a process of identification requiring us to negotiate our path between what is seen, what is sensed, and what is known.

Time production

In Xavier Le Roy's "Retrospective”, the theatrical codes of visibility and timing had to shift to those of the museum: the determined duration of the spectacle was transformed into the quasi-perennial but interrupted and mediated access to the works. [9] Le Roy used this displacement as a tool to “produce time” and to deal with permanent visibility as well as with the unpredictable duration of the spectators’ “visit”. The position every visitor was given, or was able to take, in the construction of meaning was at play, as the visitor was the receiver of a kind of memory “in progress” and a living archive. In fact the whole retrospective at once exhibited and built memory: The pieces were simultaneously re-played and interpreted, shown as a background and as a medium to construct time. The project involved the invisibility of Le Roy’s actual pieces as well as exhibiting instead the behind-the-scenes and the permanence of the pieces’ access for spectacle vivant. This was a way to answer the question of the work’s transmission into this realm: transmission in dance has always been a problem of how to keep the memory of a ballet. Either you invent notations (like Rudolf von Laban did); or you record the image of it; or you hand it on from one person to another, “teach” it as living memory in a performative way, which means to deal with ideas more than images.

Xavier Le Roy, "Retrospective”, Antoni Tapiès Foundation, Barcelona, exhibition view (Foto: Lluís Bover)

Xavier Le Roy, "Retrospective”, Antoni Tapiès Foundation, Barcelona, exhibition view (Foto: Lluís Bover)

Whose body ?

Le Roy is a choreographer who clearly intends to interpret his own pieces. [10] The fact that he is usually the very person who conceives and performs his work stresses the tension between representation (reproduction of a gesture) and act (production of the self through a gesture). Therefore, one big issue in the retrospective was the performers. Dancers and choreographers from Barcelona and from Rennes worked and rehearsed with Le Roy for two weeks before the opening. During the show the personal was clearly overcoming their narratives – even to the point of becoming sometimes too much anecdotal. Re-narrating the self may begin by first stating that one should stay unfinished: “vivant”. Appropriating a subjective position from Le Roy, thinking aloud one’s practice by describing Le Roy’s, the performer was the author of a static image, a document, more than the inventor of his or her own story. Mostly, the performers were, in the “contract” provided by the concept of the retrospective, playing the part of a very contrived passation: a possible mode of subjective emancipation through a symbolic apparatus. As any representational process is a kind of contract and refers to a kind of subjectivization process, Xavier Le Roy's "Retrospective” was configuring a “conclusion of a contract” which was also a passation or “transfer”. The performers were representatives allowing this passation to operate, not the addressees.

The one that would not play a part but live an experience was the visitor. Through the format of the three levels and the dark space, visitors were given the choice between different ways of relating to the show. They were given the opportunity to take time, to enter into a conversation, to withdraw, to shift between the levels of display, to be visible or not. The passation didn't happen between the performers and Le Roy. The scene was a space to negotiate “oneself” between various constituents in Le Roy’s project: the performers, the representation and storytelling, the time for documents and the time for happenings, the changes of levels, and the dark space allowing disappearance. Visitors could choose to be the dreamer, the dreaming, the dream. Neither a self-portrait, nor the statement of an author, the retrospective was a new experiment with dance. It created a situation for the body in which to produce meaning and knowledge, with the help of many things outside dance. In contrast to museums' tendency to exhibit dance as a way to make art look different, Le Roy's "Retrospective" allowed dance to be different, which was, in the end, a good description of the choreographer’s overall practice.

[1] Formerly the Centre choréographique national de Rennes et de Bretagne (CCNRB), the “Musée de la danse” is a manifesto in the shape of a research center, the result of Boris Charmaz's involvement in the future of dance through a history in process and accumulation of practices. In a recent publication, Charmaz said that the body of the dancer is the actual museum: a memory of all gestures it has learned and with which it has been built. This makes the place anything but a museum.

[2] It will be included in the International Summer Festival Hamburg from August 7–25, 2013.

[3] There were five dancers who performed this routine and a sixth one who didn't interrupt his or her movement, a decision Le Roy made due to the great number of visitors that made the interrupting process almost constant. This way you could also relate to a long story and enter into his work more easily.

[4] “The brightly lit performing area gives no clues to 'how to read' and the mechanical-man beginning is offset with a return to ordinary task-like activity: walk, sit, turn off tape machine. By the time you're into the contortions with the dress, we're given this extraordinary hybrid creature which confronts us with a multiplicity of interpretations. For me it alternated variously as insect, martian, chicken, watering can, caterpillar into pupa, et al.” Yvonne Rainer (email 22.12.1999)

[5] For instance, Le Roy refused to participate in the exhibition “Danser sa vie” at the Centre Pompidou in 2012. Cf. Marie Muracciole, “Exhibition/Inhibition. On ‘Paul Klee Polyphonies’ at Cité de la Musique, and ‘Danser sa vie’ at Centre Pompidou, both Paris”, in: Texte zur Kunst, 85, 2012, pp. 169–173.

[6] 20 artists and theoreticians were involved in public events open 35 hours a week in which spectators were allowed to enter when nobody had planned anything.

[7] A choreographic lecture about the shift from physical science to dance Le Roy made in his twenties, which greatly influenced both Jérôme Bel and Tino Seghal.

[8] A concert and its deconstructions: Some musician plays; some others play only the gestures without any instruments, exhibiting the choreographic aspect of performing music.

[9] As such, the show at the Tapiès Foundation was the real thing. In Rennes, the empathy between the project and the place – its didactic mission of constructing an archive of movement that deals with transmission – did not help the retrospective invent its own status. The frame, the timing, was much smaller of course, and as Le Roy puts it, “it was turning the exhibition into a simple spectacle”, which he felt to be a problem.

[10] Le Roy lent Sehgal (first a dancer for Bel and then for Le Roy) the time framing protocol of his performative actions. Moreover, Le Roy keeps up a long-term dialogue with Bel, whose practice takes dance as a point of departure for an investigation of the theatrical apparatus. Bel doesn’t need or wish to dance himself – working mostly with dramaturgy of relation built by language into the performer’s gestural productions.