Ilya Lipkin on the Photographic Alt-Real

WANNABE

The recent crisis of "alternative facts" is not a new one to art history. Indeed, one need look no farther than to the anxiety over the 'loss of truth' as digital processes divested photography of its material, indexical connection to its referent. Party to this, have always been evolving definitions and aesthetics of 'the real.'

Examining what iterations thereof we might currently see as 'true' (and why) photographer Ilya Lipkin takes up, here, a recent editorial spread by David Sims and Max Pearmain (involving the Estate of Kathy Acker), as well as the work of Josephine Pryde.

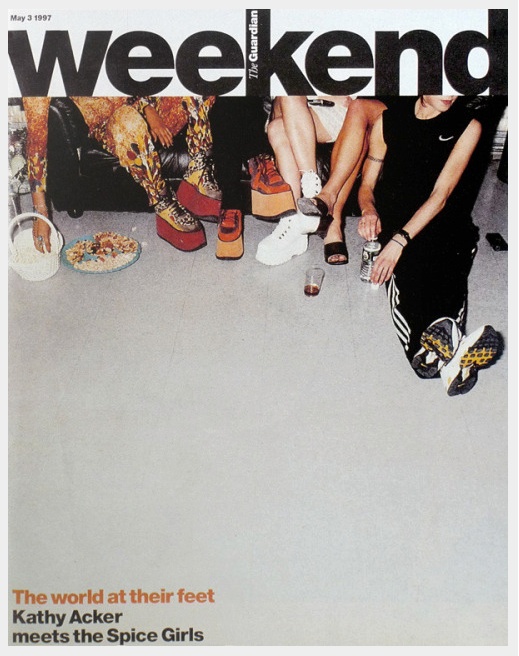

The May 3rd, 1997 cover of the Guardian’s Weekend magazine featured a single photograph of the Spice Girls, then at the height of their fame. An expanse of grey linoleum tiles bluntly reflecting the photographer’s flash takes up most of the page. At the very top of the image, directly beneath the publication’s logo, we see the Girls themselves – or rather, a saturated, contrasty arrangement of crossed legs and feet, their ubiquitous faces cropped out of the frame. This photographic send-up, shot by Nigel Shafran, was published at the culmination of a decade-long shift towards a particular kind of so-called realism in fashion photography. Rejecting the glossy, studio-crafted aesthetic of the 1980s, this ’90s iteration of the real, pioneered in part by Shafran himself, embraced an across-the-board directness, a preference for natural light (or at most a simple on-camera flash), and the casting of average people instead of professional models. In this vein Shafran’s stripped-down image, published to run with an interview of the Girls by Kathy Acker, served as the perfect foil for the band’s polished commercial persona.

The interview itself provides another contrast: that of Acker (self-described as having been “spoon fed Marx and Hegel”) contra the Girls as post-Thatcher icons of Cool-Britannia. In the piece, Acker argues that on account of the populist roots behind the Girls’ mass-cultural success, they were in an unprecedented position of political articulation on behalf of a feminist cause: Girl Power was real. And much like Shafran’s photograph, the Girls revelled in directness (theirs, a class-inflected “proleness”) that underscored their particular brand of feminist politics. From the vantage of 2016, one cannot help but feel pangs of nostalgia for their optimism. Given the steady shift of the mainstream over the past two decades towards right-wing conservatism, both the promise of effecting political change from within pop culture as well as the belief that photographic directness correlates to a ‘truer’ engagement with real life – just as much a fiction then as it is now – seems light years away.

But at the time, Shafran and many of his peers nevertheless aimed to access that truth by pushing against the perceived phoniness of 1980s visual culture and deriving “realness” from a return to a disturbingly literalist notion of the document (e.g., Nan Goldin or Mark Lebon, and the aesthetics of the late 80’s punk/indie subcultures). These young ’90s photographers also owed their look to developments in photographic technology – not the emergence of digital photography (which for a variety of reasons was not widely in use among professionals until at least the early 2000s) but rather, the refinement of compact cameras and advances in 35mm color film and film processing. Think, here, of the mid-’90s pictures of Jürgen Teller or Corinne Day. Viewing them now (the “realness effects” of vulnerability and personal intimacy in which they traded having since been normalized through contemporary social media sharing), one might miss how raw these image first seemed.

In her Spice Girls interview, Acker points out that this emphasis on the valorization of individual experience (which could easily describe aspects of Acker’s own writing), was intrinsically linked to the ideological triumph of the neoliberal turn. Indeed, the current visual nostalgia for the ’90s – pointedly evidenced, for example, in Vetements' “SUMMERCAMP” book (shot by Pierre Ange Carlotti and released this past fall); or, say, in the editorial work of provocateur Sandy Kim (Purple Magazine, the Fader, etc.) – speaks to the staying power of an anti-intellectual immediacy in photographic practice, as well as to the ever-metastasizing ‘i’-focused structure of contemporary social relations.

Many of the photographers who helped situate this look within the pages of ’90s fashion magazines are still working today. But a recent piece of editorial by David Sims (another pioneer of ’90s realism) in the Summer/Autumn 2016 issue of Arena Homme+ gave particular pause. Produced in collaboration with the stylist Max Pearmain, the story features clothing borrowed from the Kathy Acker estate. In a brief telephone conversation, Pearmain described to me his excitement in discovering Acker’s outfits, stored by a friend of hers in boxes in a LA garage: “She dressed like a prostitute,” he said with genuine enthusiasm; “it was a way to protect herself on the streets of 1980s New York.”

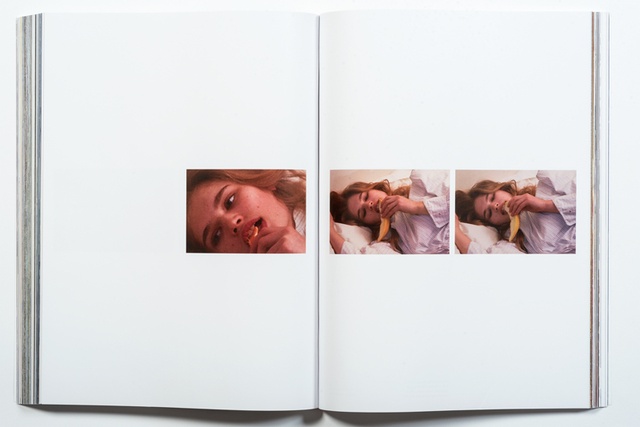

The editorial revolves around repetition, presenting multiple images of bodies in various states of dress and repose; faces and hands performing suggestive, cinematic gestures. In several instances, one must look twice to distinguish the slight crop or zoom or change in facial expression that constitutes the difference between two successive shots. These photographs are primarily operative on the level of their content, which is less the subjects depicted or any psychology their bodies might convey – or for that matter, the outfits from Acker in which they are draped (as the photographs are too small for the clothes to be clearly legible) – but, rather, the gamut of technical tropes and possibilities within studio photography today. And it is through this seeming evacuation of conventional content via formal manipulation, that these shots shed light on our current relation to the world of images.

A spread from "Sex Wars" (a collaboration with the estate of Kathy Acker) by David Sims and Max Pearmain for Arena Homme+ (Summer/Autumn 2016)

A spread from "Sex Wars" (a collaboration with the estate of Kathy Acker) by David Sims and Max Pearmain for Arena Homme+ (Summer/Autumn 2016)

If the original distinction between “document” and “picture” lay in the document’s non-aesthetic form – e.g, Atget’s Paris, Winogrand’s America – this distinction seems moot in our hyper visually-literate world. And indeed the work of both ‘street photographers,’ initially taken as raw document, soon came to represent specific (pictorial) styles. Today, the indexical imprint for a new kind of document is style itself, served up by fashion as content. This insight lies at the heart of Sims and Pearmain’s collaboration. They are aware, or at least they seem to effectively intuit, that we now inhabit Flusser's “photographic universe” – one wherein, images do not just make the world visible to humans, but rather, “[i]nstead of representing the world, they obscure it, until human beings' lives become a function of the images they create" rather than the other way around. _[1] – or in other words, a world that is fully semiotic. Practitioners like Sims have honed an approach that exploits the loss of the photographic referent, staging precise affective nuance instead. By creating images that deftly trade in the way in which form (lighting, focus, cropping, etc.) has unconsciously become shorthand for the social function of a given photograph, Sims steers the viewer towards a particular reading through technical means. On a far less sophisticated level, this is precisely what is on offer through Instagram filters – which allow users to approximate the look of the faded ’80s Polaroid, or the ’90s lo-fi disposable camera, etc. – evoking their attendant mood through the association of social memory with specific photographic technology.

'#josephinepryde not' via @tr0llslanda Instagram, 2016

'#josephinepryde not' via @tr0llslanda Instagram, 2016

Browsing Instagram, a photographic universe onto itself, someone has posted a pic taken in what appears to be an airport, or a shopping mall, of an ad depicting a manicured hand clutching an iPhone. The comment reads: “#josephinepryde not,” jokingly differentiating this commercial image from a recent series by the hashtagged artist of photos strikingly similar in their coding, wherein hands make contact with the surfaces of touch sensitive technology: phones, tablets, lamps. And it’s true, some of Pryde’s works could very nearly be advertisements. At least in part, the images are dependent on this initial confusion, as well as on the viewers’ personal capacity to distinguish between the visual logic of the ad in the airport and the details Pryde includes in her shots. In turn, these photographs frame her viewers in relation to their visual literacy; in this case, chipped nail polish or age-spotted hands breaking the verisimilitude of reading as “real” advertisement.

While Pryde’s project is too multifaceted to be reduced to singular terms, one could argue there is a kind of realism at work in her images as well, albeit one that is strikingly different from that of the ’90's generation. By repeatedly appropriating and then disrupting the conventions of a particular photographic genre (be it advertising, fashion, child portraiture, or the “fine art” photograph itself), Pryde plays on our internalization of the commercial aesthetic and our conflation of this aesthetic with a kind of visual truth. The uncanny effect of encountering one of her photographs stems from this very tension between our ever self-updating visual lexicon and her knowing manipulation of its usage.

Josephine Pryde, "Here Do You Want To," 2014

Josephine Pryde, "Here Do You Want To," 2014

Central here is the fact that the language of photography is one thoroughly and inescapably inflected by capitalism. We need only to think of the millions of selfies, sunsets, food images and pictures of glowing, healthy children circulating through our smartphones, emulating their professional counterparts in commercials for makeup, real estate, Baby Gap, etc. Or, conversely, of the I Am Nikon advertising campaign, in which non-professional Nikon customers were gifted DSLR’s to film exceptional moments from their everyday life. (The footage, consisting of the aforementioned usual suspects, was subsequently edited into a short film whose loose, amateurish camera movements, submitted by actual amateurs, functioned as a signifier for the authenticity of Nikon products.) This particular commercial strategy deftly attempted to play on the fact that, as the neoliberal social experience takes photography as it’s material support, it’s only through the objectification of the personal as content, that one is able to identify as active with the present social economy.

If a realist project were to exist in contemporary photographic practice, confronting the relationship between the photograph and the broader structural logic that determines its place in our world of images could be a good place to start. If we agree that capitalism dictates what is perceived as real, it would then ostensibly be the role of the photographer today (and arguably, also, the responsibility of the viewer) to question that visual reality on its own terms, through its stylistic and formal coding. And it is in this space, rather than in any given piece content – not in the unplugged look of mega pop stars nor the exhumed wardrobe of an anarchist, feminist poet – that the radical gesture can play out.

Notes

| [1] | Villém Flusser, (1983) “Towards a Philosophy of Photography,” (London: Reaktion, 2000), p. 10 |